According to government records, when the scheme was announced, it had around 2.63 crore applicants. Initially, the welfare scheme amount was disbursed without any scrutiny. By February 2025, the scrutiny process reduced that figure by 11 lakh to 2.52 crore. In March, the number was further reduced to 2.46 crore.

However, when further verification began—albeit at a snail’s pace—nearly 26.34 lakh names were found ineligible, leaving 2.25 crore eligible women. Now that scrutiny has been initiated, it has been observed that even men enrolled in the scheme. This raises a key question: were lapses in screening due to government oversight, administrative flaws, or both?

With over ten percent of the original list being faulty, both ineligible women and men took advantage of the scheme. More names will have to be deleted once the entire verification process is complete. Such casualness with data and spending will certainly not go down well with the common man.

At a time when the government is pouring over Rs 36,000 crore every year into the scheme, the minimum expectation of citizens is to make it foolproof. This is no longer a technical challenge. Verification to weed out ineligible beneficiaries, in today’s digital age—where Permanent Account Number (PAN), Aadhaar, and bank accounts are all linked—is no longer a tedious or uphill task. It can be completed within a few weeks, no matter the size of the database.

In neighbouring Madhya Pradesh (MP), Aadhaar-linked, Direct Beneficiary Transfer (DBT)-enabled accounts were made mandatory for benefits, which helped reduce leakages. Since the scheme was already in place in MP, the Maharashtra government could have taken a cue from them and implemented similar measures, as the format for plugging leakages was readily available. In fact, any government could have cleaned up the rolls within a week.

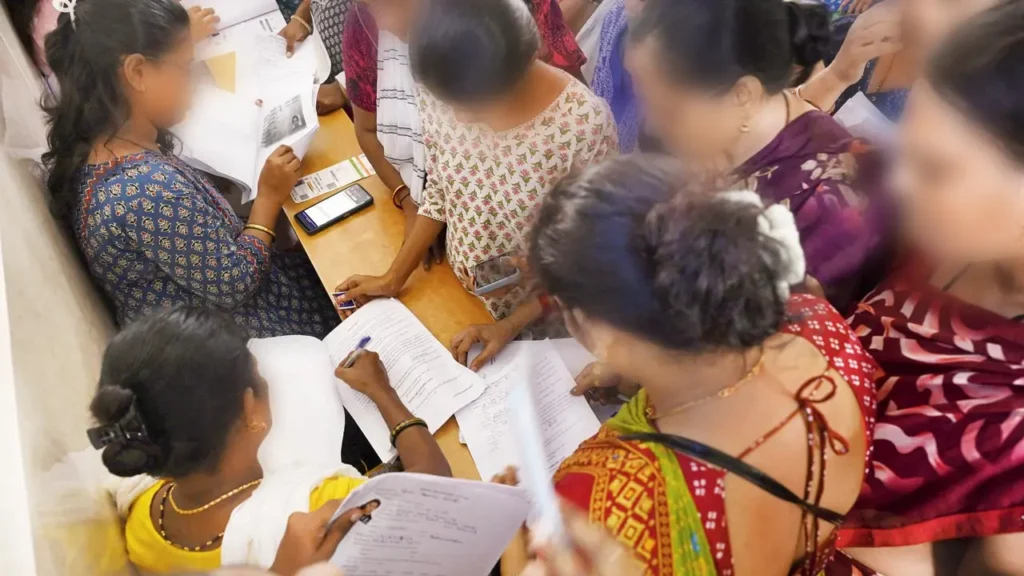

But the mandatory e-KYC process was initiated just 10-15 days ago—nearly 15 months after the launch of the scheme. The real struggle for many beneficiaries is that they lack smartphones, internet connectivity, and more importantly, knowledge of how to complete the process independently. These women need assistance to get verified as per government norms.

In the past, the scheme has even sparked tensions within the ruling party, with several MLAs and ministers complaining that delays in the disbursement of development funds were being blamed on the popular scheme.

When the programme was announced, it was estimated to cost Rs 45,000 crore. However, during the 2025-26 budget, the allocation was cut to Rs 36,000 crore, highlighting the strain the scheme was placing on the finance department and the state’s rising debt.

So, what is coming in the way of finalising the list of eligible beneficiaries? Is it administrative inefficiency or a deliberate political move?

The delay raises questions on whether the scheme is genuinely to empower women or if it is turning out to be a political cushion padded with taxpayers’ money. The obvious suspicion is that the delay is not accidental but political.

Why risk alienating names before the mini elections—the local body polls? A bloated list of beneficiaries will only help the ruling regime gain electoral mileage during the Zilla Parishad (ZP), panchayat, municipal corporation, and council polls.

So why is the verification process moving at a snail’s pace?

The Ladki Bahin scheme was a game changer. The idea changed the fortunes of BJP, Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena, and Ajit Pawar’s faction of the NCP. After the Lok Sabha poll debacle for the BJP and its allies, the welfare scheme turned out to be a political jackpot for the Mahayuti in the Assembly polls.

The Supreme Court has set January 31, 2025, as the deadline for local body polls. For Mahayuti, these polls are a test of strength before the 2029 Lok Sabha polls.

Aware of this litmus test, keeping the Ladki Bahin list longer works for the ruling regime, given how crucial women voters were in swinging the 2024 Assembly polls.

This year, the state, in its budget, has estimated a debt of Rs 9.32 lakh crore for the financial year 2025-26—the highest in the state’s history. This simply means that even as the state government’s debt is rising, governance still takes a backseat, and vote-bank politics takes precedence and the driver’s seat.

—

Sanjeev Shivadekar is Political Editor, mid-day. He tweets @SanjeevShivadekar.

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com.

https://www.mid-day.com/news/opinion/article/a-list-delayed-is-an-election-won-23596003