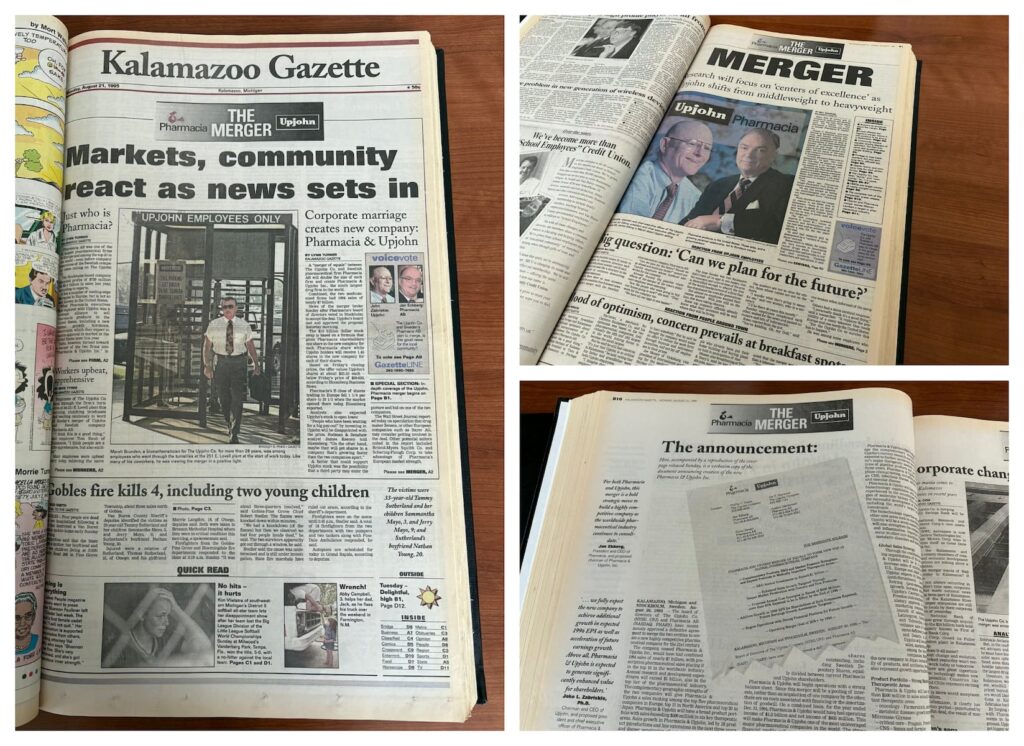

This story is part of the Southwest Michigan Journalism Collaborative’s coverage of equitable community development. SWMJC is a group of 12 regional organizations dedicated to strengthening local journalism. To learn more, visit swmichjournalism. com. KALAMAZOO, MI It was 30 years ago that Kalamazoo-area residents woke to news that hit like a collective gut punch. The Upjohn Co. the pharmaceutical company based in Kalamazoo County since 1886 — announced it was merging with Pharmacia, a Swedish drugmaker. At the time of the 1995 merger, Upjohn employed almost 7, 000 people locally. But Upjohn was more than just the county’s largest employer and taxpayer. For decades, it was the community’s safety net, its problem solver, its sugar daddy, the region’s dominant entity. With the merger, all that was about to change. And change it did. Over the next seven years, the headquarters moved to New Jersey along with 600 administrative and marketing jobs, Upjohn was dropped from the corporate name and then Pharmacia was bought out by Pfizer Inc. in 2002. The biggest blow came in 2003, when Pfizer closed its Kalamazoo research and development operations a loss of 1, 600 well-paying jobs, most in downtown Kalamazoo. “We’re not getting nicked. We’re getting whacked,” Barry Broome, then head of Southwest Michigan First, Kalamazoo County’s economic development agency, said at the time. The news was especially devastating because it occurred amid other economic blows: More than a thousand jobs lost with the 1997 sale of Kalamazoo-based First of America Bank; 4, 000 laid off with the 1999 closure of the General Motors Comstock plant; and hundreds more jobs evaporated with the shutdown of five area paper mills between 2000 and 2004. Meanwhile, the downtown Kalamazoo Mall was hammered by the closure of the Jacobson’s and Gilmore’s department stores in 1997 and 1999. Residents worried Kalamazoo was yet another Rust Belt city spiraling into decline. Would Kalamazoo become the next Benton Harbor? The next Flint? “It was horrible,” said Hannah McKinney Apps, a Kalamazoo College economic professor who was Kalamazoo vice mayor during that time. With each announcement, “you thought, ‘Oh, the sky’s falling. The sky is falling.’ And yet it didn’t.” Indeed, in a quarter-century where many Michigan urban hubs have struggled, Kalamazoo has been noteworthy for its resilience. Among the keys to the community’s stability: The loss of Upjohn’s considerable corporate philanthropy has been offset by philanthropy from the Upjohn and Stryker families, as well as anonymous donors who have spent more than a $1. 3 billion dollars on local initiatives in the past two decades. Kalamazoo is the only American city where private benefactors cover college tuition for its public high school graduates, subsidize property taxes and provide new mothers with $500 a month during a baby’s first year. Pfizer remains a major presence in Kalamazoo County, employing about 3, 000 at its Portage facility, the company’s largest manufacturing plant. Zoetis, a Pfizer spinoff that specializes in animal health, has another 1, 500 workers in Kalamazoo County. As Pharmacia/Pfizer were downsizing here, Stryker Corp. was undergoing explosive growth. The Portage-based medical technology manufacturer now employs around 4, 000 in Kalamazoo County. Community leaders have made concerted efforts to boost and diversify the local economy, including economic development initiatives involving Western Michigan University and Kalamazoo Valley Community College, as well as the area’s two regional hospital systems. When she first moved to Kalamazoo in the late 1990s, political scientist Michelle Miller-Adams recalls “the general impression was the city was struggling. You had this massive corporate merger, the plant closures, the loss of businesses on the downtown mall, all your typical signs of decline.” It seemed to follow a familiar pattern in which “jobs go, people go, amenities go and then cities get hollowed out,” she said. But that didn’t happen in Kalamazoo, as community leaders focused on “major things that would make this community stickier,” things would make individuals want to stay, Miller-Adams said. “There was a lot of stuff happening behind the scenes to forestall the worst consequences,” she said. “And that’s what made the difference for Kalamazoo. There were people who knew what was coming and were very active in thinking about strategies to mitigate the impact. “People were taking steps. They weren’t just reacting.” Upjohn’s impact The Upjohn Co. was founded in 1886 by Dr. William E. Upjohn and three of his brothers. Over the years, it developed such blockbuster drugs as Xanax, Halcion, Motrin, Rogaine, Kaopectate, Mycitracin and Cortaid. In the 1950s, it was Upjohn that developed the process for the large-scale production of cortisone and prednisone. Meanwhile, The Upjohn Co. and Upjohn family played a huge role in shaping the Kalamazoo community. It was W. E. Upjohn, for instance, who urged the city of Kalamazoo to become one of the first to adopt a city manager form of government in 1918. Likewise, he was behind the creation of the Kalamazoo Community Foundation, providing the first $1, 000 in seed money. Until 1987, the foundation’s CEO was on the Upjohn payroll. And there was more, much more. The Upjohn Co. as well as Upjohn family members had their hand in almost every cultural institution and civic activity in the area, from establishing the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, to seeding the money for the Kalamazoo Area Math and Science Center, to bringing professional hockey to Kalamazoo. “In Upjohn, you had a partnership that you don’t see in a lot of communities,” said Fred Upton, Kalamazoo’s congressman from 1992 to 2024. To say The Upjohn Co. and the family was influential is an understatement, said George Arwady, publisher of the Kalamazoo Gazette from 1988 to 2004. “A lot of the progressive nature of the politics and economy of Kalamazoo come from the very progressive leadership of The Upjohn Co. and the family,” Arwady said. Throughout the 20th century, “you had Upjohn people at the center of everything. And to a certain extent, they still are.” An Upjohn even had a key role in Stryker’s explosive growth, according to Arwady. Stryker was founded in 1941 by Dr. Homer Stryker, an orthopedic surgeon at Borgess Hospital. In 1976, the firm was thrown into crisis when Lee Stryker, Homer’s only child and by then the company’s CEO, was killed in a private plane crash, leaving Stryker without a leader. Stryker’s board chair at the time was Burton Upjohn, great-grandson of Henry Upjohn, a co-founder of The Upjohn Co. After Lee Stryker’s death, Burt Upjohn helped run Stryker Corp., and he and his wife Betty also “were absolutely central to the recruitment of John Brown” as Stryker’s new CEO, Arwady said. Over the next 32 years, Brown grew Stryker Corp. from a family-run company into an international powerhouse. When Brown started in 1977, Stryker had about 400 employees and $17 million in annual sales. It now has more than 50, 000 employees worldwide and had $23 billion in sales in 2024. “The blossoming of Stryker is an incredible success story, and a lot of the leadership of Stryker had the same kind of feeling as the Upjohn leadership,” Arwady said. “They’re business people who want to make a buck, but also they’re very progressive, very community-oriented.” Local philanthropy But even as corporate philanthropy ebbed in Kalamazoo, that void has been filled by individuals, primarily Ronda Stryker and her husband Bill Johnston. The oldest of Lee Stryker’s three children, Ronda is worth an estimated $8 billion, thanks to Stryker’s explosive growth. The couple, who met as teachers at Kalamazoo’s South Middle School, still live in the area. Bill Johnston has become a prominent leader in Kalamazoo’s economic development, sometimes joining forces with Bill Parfet, a great-grandson of W. E. Upjohn. In 2011, for instance, Ronda Stryker donated $100 million to establish a medical school at Western Michigan University while Parfet donated the facility, part of Upjohn’s former R&D space in downtown Kalamazoo. In 2017, Johnston and Parfet created the Kalamazoo Foundation for Excellence, a nonprofit seeded with a $70 million initial donation. The foundation, which has since received a $400 million endowment from an anonymous donor, reduces Kalamazoo city property taxes and provides funds for “aspirational” community projects. But the philanthropic gift that really put Kalamazoo on the map was The Kalamazoo Promise, unveiled in November 2005. Funded by anonymous donors, the sweeping scholarship program covers undergraduate tuition and fees at almost any Michigan college for graduates of Kalamazoo Public Schools. Starting with the KPS Class of 2006, The Promise has paid almost $250 million in tuition for almost 9, 000 students. In addition to transforming the lives of individual students, it’s also credited with stabilizing KPS enrollment, which has been a huge challenge in Michigan’s other urban school districts and a major factor in the decline of urban hubs. The Promise has gained national attention, including a 2010 visit by President Barack Obama, who gave the commencement speech at Kalamazoo Central High School’s graduation. The program celebrated its 20th anniversary this month. Among those at a celebration dinner was Rianna Clay-Valdez, a Promise recipient who graduated from WMU in 2024 and is now a financial analyst at Stryker. She’s part of a wave of Promise grads who have settled in Kalamazoo after college, wanting to be part of the community that gave them a huge boost. “Growing up, you always thought about getting out of Kalamazoo,” she said. “But now you’re seeing the phase where not all of us want to leave. We want to stay because we see the potential and the purpose here, just like The Promise saw in us.” The Promise is the community’s most high-profile anonymous gift, but there’s a string of others, including $550 million for WMU, the $400 million endowment for the Kalamazoo Foundation for Excellence and $100 million to fund a new countywide high school for career training. Other factors While private philanthropy has softened the blow of plant closings and business mergers, many also credit the work of local business leaders in the 1990s and beyond to diversify the local economy. That includes the creation of the WMU Business, Technology and Research Park next to WMU College of Engineering. The BTR Park opened in 2003, with the intention of trying to keep Pfizer scientists in the area and encourage high-tech startups. The park houses about 40 businesses and has created or retained about 1, 400 jobs, according to WMU. The BTR Park “has birthed a lot businesses,” Miller-Adams said. “Those businesses weren’t the same thing as having The Upjohn Co. here, but I think it’s really important that some people ended up staying.” KVCC also has played a role in community development. Since the mid-1990s, it’s opened three satellite campuses, including one in Texas Township to offer specialized workforce training for local employers and two in downtown Kalamazoo, one along Rose Street and the other next to Bronson Methodist Hospital. Upton compares the role of higher education in Kalamazoo to South Bend. “Notre Dame is a great university, but in my view, they feel removed from the community,” Upton said. “And if you look at South Bend today, I’m sure glad that we have Kalamazoo and not South Bend. South Bend has a bad downtown; there’s nothing going on. Whereas WMU and KVCC are really integral to the city,” especially with WMU medical school in the old Upjohn facilities and the new event center under construction downtown to house WMU basketball and hockey. “That new facility they’re building, that’s going to be a mainstay for Kalamazoo,” Upton said. “It’s very exciting for the future.” Kalamazoo County also benefits from the fact Pfizer continues to be a significant presence, thanks to the manufacturing plant in Portage. Arwady recalls how community leaders lobbied hard to keep the plant open, pointing out that manufacturing of pharmaceuticals requires certifications from the federal Food and Drug Administration. “It’s easier to add onto a plant when you already have those approvals and infrastructure in place than to build somewhere else,” Arwady said. “So Kalamazoo is still benefiting from the fact that Upjohn over the years made very large and critical investments in Kalamazoo County. Pfizer obviously did the math that showed it made sense to keep” the manufacturing plant. In fact, Pfizer has continued to upgrade and expand manufacturing operations here, and the world’s first COVID vaccines were made in Portage. Looking to the future To be sure, Kalamazoo still has its problems there are still struggling neighborhoods and housing affordability and homelessness are growing issues, said Apps and Miller-Adams. There’s also the realization that the world has changed, particularly in a global economy and where larger metro areas such as Grand Rapids have an inherit advantage over Kalamazoo because of access to airports, a job market that can more easily accommodate dual-career couples and a broader choice of housing and schools. “We’ve done so many things that have been successful” in the past quarter-century, “but none of them took us back to the heyday,” Apps said. “It hasn’t turned Kalamazoo into a high-growth mecca.” Moreover, change is inevitable. Stryker could move its headquarters elsewhere. The current crop of philanthropists won’t live forever. Economic downturns will happen. That said, the Kalamazoo area is still viewed by many as a desirable place to live. The university, the two regional hospitals, The Kalamazoo Promise and a vibrant arts and culture scene unusual for a community of its size continue to draw and retain residents. Kalamazoo “really is a garden, and we’ve had good gardeners,” Upton said. “It’s a lovely place to call home.” Want more Kalamazoo-area news? Bookmark MLive’s local Kalamazoo news page.

https://www.mlive.com/news/kalamazoo/2025/11/30-years-after-upjohn-merger-kalamazoo-area-proves-its-resilience.html

30 years after Upjohn merger, Kalamazoo area proves its resilience