Karl Marx’s famous quip that history repeats itself, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce,” aptly fits the so-called revival of miniature painting in Pakistan.

The process began in the early 1980s at the National College of Arts (NCA), an institution established by colonial rulers in 1876 and later revamped by faculty brought from abroad. Led by Professor Mark Sponenburgh, the teachers introduced a new pedagogical structure, compartmentalising indigenous practices into three departments: fine art, design, and architecture. This was a complete break from the tradition of object-making, which had been labelled craft for convenience.

Although students were encouraged to copy and document historic items, traditional artefacts, and heritage sites, the approach was largely that of an outsider: conquering unfamiliar territory, exploiting its resources, controlling its aesthetic products, and disrupting its natural and meaningful cycle. Once this connection is severed, the language of indigenous image-makers becomes the mumbling of a mute, disempowered, and dishonoured people—until they relearn ancestral skills through the lens of outsiders, in pursuit of their approval and respect.

The history of miniature painting illustrates this well. Before the arrival of Western armies in the subcontinent, Indian miniature painting was recognised as an independent, authentic, and sophisticated art form. Magnificent, original, and refined manuscripts were produced in the courts of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan.

Later, with the decline of the Mughal dynasty, the practice waned, surviving only in the Rajput princely states of Rajasthan and Kashmir. With the arrival of foreign rulers from distant shores, traditional miniature painters either adapted the imagery of new patrons into old settings or imitated European painting. This body of work across India reflects not a decline in skill, but a fall in status.

Cultures have always borrowed elements from others, absorbing them to expand their vocabulary—a phenomenon as common in art as in language, and one evident during the reigns of the three great Mughals. Masters such as Bichitr, Abul Hasan, Daswanth, Kesu Das, Farrukh Beg, Manohar, Mansur, Nanha, and Balchand assimilated naturalistic figures, atmospheric landscapes, European narratives, and Christian themes into miniatures. They enriched aesthetics and extended content while remaining rooted in a particular worldview.

They were able to do so because these miniaturists, working for sovereigns, were neither subjugated by conquerors nor detached from their soil and subjects.

However, new patrons altered the perception of native painters, who began to regard local expression as naive, primitive, unsophisticated, or merely decorative—like craft pieces. This mindset persists today. Functional objects from our past are reproduced for sale in expensive shops: placed on mantelpieces or hung on walls rather than used to keep bread warm, carry grain, or serve as bedding. They have become relics of a lost past, forged for a foreign clientele who spend a few nights in a five-star hotel and never return.

The same tendency can be seen in miniatures produced in recent years. Establishing miniature painting as a major discipline in the Department of Fine Arts, NCA initially trained some highly original artists who studied the traditional course but went on to innovate.

With a few exceptions, artists such as Imran Qureshi, Shahzia Sikander, Ambreen Butt, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Talha Rathore, Hasnat Mehmood, Saira Wasim, Muhammad Zeeshan, Waseem Ahmed, and Tazeen Qayyum no longer create work that can be strictly categorised as miniature painting. Instead, their practices include large-scale canvases, mixed-media compositions, installations, video projections, photography, digital prints, and performance.

In this sense, these artists are heirs to their predecessors in the early Mughal courts, who incorporated diverse idioms in response to the sensibilities of their changing times. This spirit of inquiry, investigation, and openness—so visible in the classical period of Indian miniature painting and later in its initial rebirth among the first generations of artists from the late 20th century—has in recent years begun to fade.

For this, commodification of art, market pressures, and increasing alienation from immediate realities are to blame.

Take, for example, the use of colour. Painters of the Mughal courts employed pigments that were not merely shades on a palette but extracted from—and thus imbued with the essence of—plants, stones, and other natural ingredients drawn from specific locations. A viewer of those folios could often identify the origins of the hues themselves.

Today, a practical solution is industrial paint, imported from Europe or North America. Yet a petal, a blade of grass, or a grain of rock from this land can scarcely be transmuted into a tint manufactured thousands of miles away.

The result recalls the predicament of countless students in former British colonies, struggling to visualise daffodils while reciting Wordsworth in their English language classes.

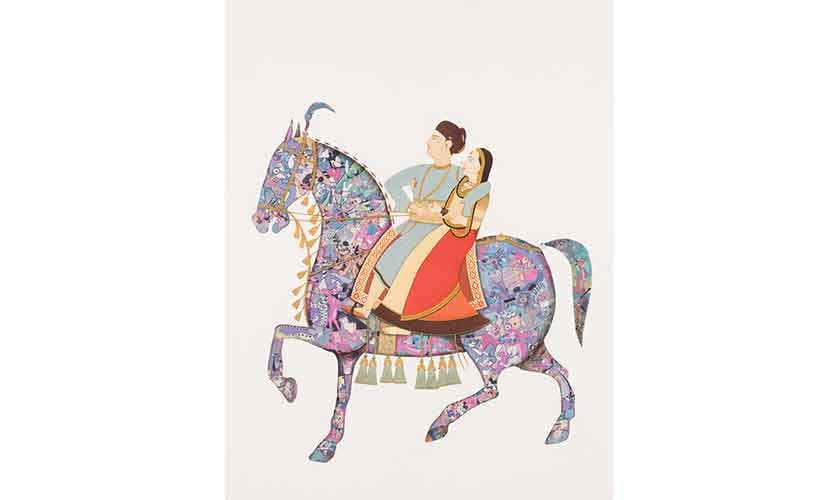

These days, a number of artists—whether recent graduates of miniature painting or fellow travellers on the neo-miniature bandwagon—aspire to emulate the past, though often without the necessary background, exposure, or skill. The result is mimicry. One encounters work, large and small, filled with stock motifs: the profile of a king, the head of a horse, floral patterns, or battling elephants and horses.

The intentions of those who seek to preserve and reimagine the past are understandable—even admirable. But when heritage is reduced to an exotic football, it becomes something to be kicked, headed, and tossed about in every direction.

On a sports field, the goals are at least clear. In the arena of art and culture, however, they are ambitious, complicated, and exhausting—both for those striving towards them and for the spectators.

Heritage, once refined, risks being remixed into a stream of saleable kitsch.

This tendency has often been visible in the work of Farhat Ali, Asif Ahmed, and more recently, in Abid Aslam’s solo exhibition. In Aslam’s work, rulers and beasts were rendered in gouache and gold leaf, with punched, flower-shaped paper used to fill in the imagery.

In its exuberance and method of cramming small units together to create a larger picture, his work was not unlike the red building, part seminary, part school, that one passes on the road to Murree. With its roof crammed with multiple round forms, it aspires to domes—an architectural elegance developed by Muslim builders to signify ascent to the divine—but ends up looking more like a cluster of painful blisters.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1346545-post-colonial-miniature-painting